Men, beware! In Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, Eva Green is treacherous, deadly and alluring enough to turn a polar ice cap into a cloud of steam. Her character has a name – Ava Lord – but she might as well be called simply Femme Fatale. She is just the latest in a long line of cinematic devil women who beguile viewers as surely as they beguile their weak-willed prey.

The appeal of the archetype is obvious enough: who wouldn’t want to watch Eva Green wrapping Josh Brolin around her little finger, among other body parts? But the femme fatale doesn’t just give audiences a delectable taste of forbidden fruit. Dr Catherine O’Rawe of Bristol University is the editor of an academic survey of the subject, Femme Fatale: Images, Histories, Contexts, and she argues that such fictional seductresses reflect society’s mixed feelings towards independent women.

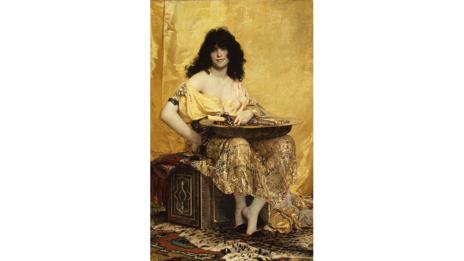

“The figure of the female temptress is as old as Eve,” says O’Rawe. “But the femme fatale as we understand it emerged in the late 19th Century, when the term was applied to a range of fin-de-siècle figures such as Salome, Rider Haggard’s She and Bram Stoker’s female vampires. What’s striking is that these figures arose at the same time as concerns about emancipated women occupying the public sphere.”

The dangerous feminine seductiveness of Salomé, painted by Henri Regnault in 1870 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

There were similar concerns in the air during the femme fatale’s big-screen heyday. The movies have always featured wicked women: in 1915, Hollywood’s original ‘vamp’, Theda Bara, ensnared and destroyed a respectable Wall Street lawyer in A Fool There Was. But it was in the 1940s that such film noir classics as Gilda, The Killers, Murder, My Sweet and Double Indemnity brought us the definitive femmes fatales: Rita Hayworth, Ava Gardner and Barbara Stanwyck at their most hazardously alluring. Sometimes evil, sometimes in thrall to a villainous male, the vamp in these films used her hypnotic eroticism to get what she wanted – up to and including murder. She may have been a fantasy, says Dr Ellen Wright, a film noir specialist at the University of East Anglia, but she personified real issues.

Barbara Stanwyck is enticingly dangerous in Double Indemnity (Universal Home Entertainment)

Home alone

“During World War II,” says Wright, “America needed its female populace to take up more jobs in the public sphere, even jobs that had once been designated as ‘men’s work’. Women were shunted about the country to where work of national import was available. But, in many instances, they were being paid better wages than they’d ever received before. You can see why many of them wanted to enjoy their leisure time rather than stay at home in the way they had done prior to the war. As a result, women’s leisure and women’s sexuality were a very hot topic in wartime America: just what were women getting up to [while] their men were away? Were they disease-ridden good-time girls or slovenly mothers? In a climate of paranoia, as there always is in war, it’s not surprising that the femme fatale became a popular figure in cinema.”

The precise message that 1940s moviegoers were supposed to take from the femme fatale is a question which has been studied by Professor Mark Jancovich, the co-author of Defining Cult Movies. “There was a feminist argument that the femme fatale was an attempt to demonise the independent working woman of the war years,” says Professor Jancovich. “She has been seen as part of the propaganda designed to push women out of men’s jobs and back into the home. But I’d argue the exact opposite of this. These films are actually demonising the women who didn’t go out to work during the war. Femmes fatales aren’t the good, spunky modern girls who work in factories. They’re the lazy good-for-nothing stay-at-homes who won’t take any public responsibility and who lounge around their husbands’ houses in their lingerie, living off their husbands’ money.”

Are films like The Killers more about another era of film-making than they are about social commentary? (Criterion Collection)

Whichever kind of woman was being demonised by such misogynistic caricatures, the irony is that femme fatales came to be loved rather than hated – and not just by smitten male viewers. “As a female filmgoer,” says Dr Wright, “I see her as an incredibly powerful and wily character who not only drives the narrative, revels in her sexuality and looks utterly fabulous, but who ultimately sees the system for what it is and absolutely refuses to accept her place within it. Whether or not she is punished for her actions – and let’s face it, she invariably is – I still think she carries a hugely empowering, invigorating message.”

Shades of grey

By the 1950s, as America’s wartime unease had faded, so did the femme fatale, although she has never disappeared completely. In 1966, she supplied the title of a much-covered Velvet Underground song. (“Little boy, she’s from the street / Before you start, you’re already beat....”) And, on film, she was particularly prominent in the 1990s, when she was embodied by Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, Madonna in Body of Evidence, Demi Moore in Disclosure and Nicole Kidman in To Die For. Again, this resurgence has been attributed to contemporary anxieties. In the conservative America wrought by Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush, Hollywood was happy to supply cautionary tales of liberated women – tales, says O’Rawe, which “require the woman to be punished for overstepping society’s limits”.

Sharon Stone helped revive the femme fatale during the 1990s in Basic Instinct (Artisan Home Entertainment)

Hollywood has hardly given up on sexism since then, but the femme fatale is seen less often today, except in a knowing, ironic context. It’s no coincidence that Eva Green’s character in Sin City: A Dame to Kill For shares her first name with Ava Gardner, the leading lady in The Killers. The new film, and others like it, are less about current social issues than they are about harking back to the movies of another era. Perhaps it’s a change that had to happen. After all, it’s hard to sell a narrative about illicit lust when divorce is no longer taboo. And it’s hard to sell voracious female sexuality as being exotic and destructive when it’s the selling point of the world’s biggest mainstream pop stars: “If you Google ‘femme fatale’,” notes O’Rawe, “the first result that appears is the Britney Spears album from 2011.”

But if sightings of old-fashioned femmes fatales are a rare treat these days, that’s not to say that films are running short of mysterious, deadly seducers who promise to spice up their admirers’ unsatisfying lives. In the place of dames to kill for, we have Christian Grey in Fifty Shades of Grey and Edward Cullen in Twilight – who is, of course, literally a vamp. Women, beware! The homme fatale is here.